Haha… sounds like a real treat huh?

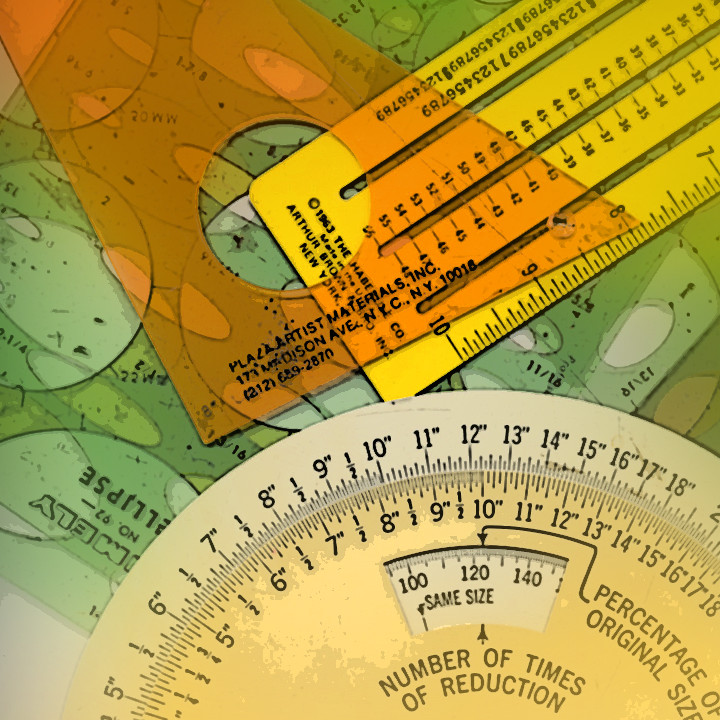

I don’t know a lot about a lot of stuff, but I know a lot about the way design was done before desktop computers. I have opaqued negatives, cut Amberlith, I owned a Goodkin Lucigraph, could identify a Lectro-Stik by its smell alone, and have spent over twenty hours (straight) using an X-Acto Knife to adjust the spacing between body text letters on a double-truck newspaper ad. I KNOW some stuff about that.

So I’ve been keeping my eye on a project that originated on Kickstarter a couple of years ago titled Graphic Means, A History of Graphic Design Production. Its director and producer Briar Levit told us, “It’s been roughly 30 years since the desktop computer revolutionized the way the graphic design industry works. For decades before that, it was the hands of industrious workers, and various ingenious machines and tools that brought type and image together on meticulously prepared paste-up boards, before they were sent to the printer.

The documentary, Graphic Means, which is now in production, will explore graphic design production of the 1950s through the 1990s—from linecaster to photocomposition, and from paste-up to PDF. ”

I wrote to the film’s director and producer Briar Levit in 2015 to make a point I hope the filmmakers took into consideration…

“I read about Graphic Means and watched the Kickstarter. It got me thinking.

I started as a designer and pasteup artist in the 1970s. Though I’m sure you’ve recognized this, I would emphasize that the production processes of any given environment were dictated by the type of equipment you had access to. In other words, the tools determined the scope of the outcome.

And the tool sets were always in flux and could be very different at each individual stat house, design studio, text typesetter, headline typesetter, ad agency, retoucher, and so on–they were often all separate businesses and each individual place had its own way of doing things.

At one design studio I worked at we had an IBM Selectric (a serious investment), so almost all of our text type was created using an IBM Selectric.

At a TV station we had no headline typesetting equipment, so we used Presstype.

Some shops used Rapidographs, others used ruling pens and ink. Some used rubber cement, others used waxers.

My point is, in addition to it being as much (or more) craft as creativity, designing in the 60s, 70s, and 80s was a resources thing. Today, everyone uses much the same tools–so to some degree, I suppose that we see what today’s tools are good at creating.”

She acknowledged the importance of that distinction and said someone else she had interviewed and made much the same point.

It makes you wonder if today, because we are all using the same tools, if we aren’t missing something significant—i.e. seemingly 25 percent or more of new websites look like, not surprisingly, the templates/CMSs they were created using.

You look back at the proliferation of, for example, steel engravings two hundred years ago and you think of how many skilled artisans there must have been to produce so many. Those folks were forced by craft to understand a whole different level of shape and form and composition. Now, I’m sure lots of us are only producing stuff that rasters and vectors can reproduce.

But that’s a different film.

Graphic Means has been screened at a couple of events in recent months so it sounds as if the release is imminent.

Here’s the official trailer…

Thoughts?